The camera was not invented. Rather, that mass produced device that captures fragments of light is a diffuse chemical accretion of the momentous. The repercussions of this development are achingly underappreciated. Users and consumers of photographs (be they acetate or binary) are dissipated within momentous optic calcium. That is, moments have stopped; the momentary is no longer operative. The evidence for this is copious. We first noticed this collapse of aesthetic duration in Paris in 2013 whilst observing the ostentatious photography of notable landmarks. The term Cliché Ennui was developed to describe such mediated indulgences, as it registers a valence of reproductive listlessness.

This did not begin with Intragram or ViewTube, rather these platforms are (valiant?) responses to the cessation of experience—dead time. How does a durationless organism persist? [Answer:] By fabricating a hypothetical alterity into which it may unfold. Digitized sociality is simply the residuum of this hypothetical.

This is not social critique. This is an interrogation of biophysical causality. In short, so much light has been captured and ossified in durationless media that it has accrued a weight of its own. The density of this accrued matter has a somewhat perpendicular effect to the celestial black holes inferred from the cavities of lapsed gravity. While it is not entirely clear what happens to the light captured by black holes, the result of reproducing optically captured light is quite apparent. It has opened up a causal trajectory of hypothetical duration—a proof universe.

An incorrect history may suggest that the alleged invention of the device known as the camera (be it Eastman’s in 1889, Chevalier’s in 1841, Giroux’s in 1839, or Niépce’s in 1826) has bred or unleashed this predicament. A more accurate history would suggest that the camera is simply a neo-appendage used to supplement paralyzed senescence via ocular stimulation. That is, the camera is a lung through which biological respiration is carried out. If not for the camera and its output, the energy displacing exercises of our species would have led to the cessation of entropic life over a century ago. Though an exact date is unattainable (because of the dissolution of moments), it would be more precise to designate the appearance of the camera as the onset of our current hypothetical causality. Life in this sector was pulled through an aperture at some point (or across a series of points). We are now on the other side of the lens. We see things differently on this side, most noticeably time.

The received historiography of the camera erects a narrative about capturing moments. The camera doesn’t do this. Memories, language, painting, dances—these are technologies that hold the momentous. Dancing is a momentous experience—an experience of the momentary that can be unleashed on the universe under the proper conditions. Rather than capture moments, the camera projects forward a façade of moments into a two-dimensional duration. Reality on paper (or screen or canvas). Why else would one take a photograph of the Eiffel Tower or the Mona Lisa? These landmarks do not need to be captured. They already exist as stable media. They are photographed in order to build the hypothetical alterity into which our actions precede, having no recourse to experience as a conduit of moments. Why are there stock photographs? To deploy the suggestion of a moment when our depletion beckons.

The reasons for the build-up of calcified light rot leading up to the appearance of the camera are not entirely clear, but a few trajectories avail themselves… To be explored subsequently.

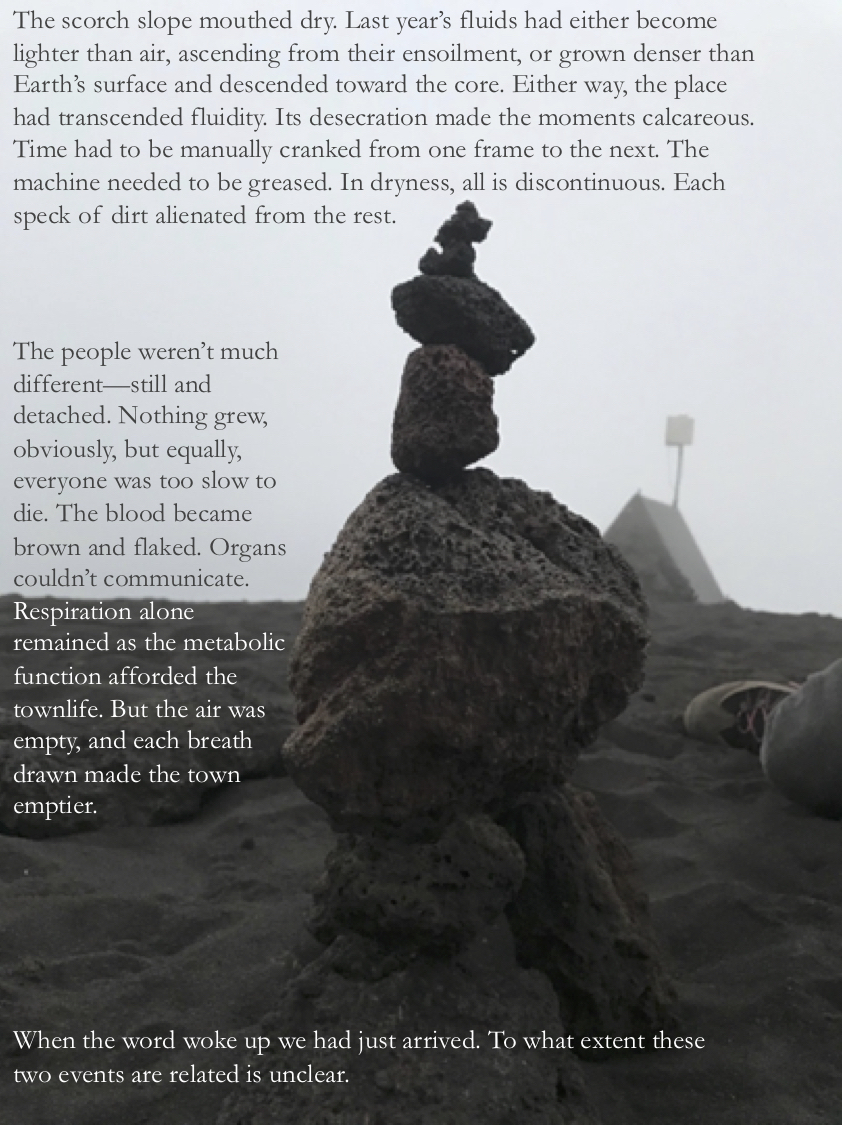

Attached below are efforts to recalibrate images extracted from hypothetical duration and supply them with a blend of momentum.